For chef Joël Robuchon, resting on his laurels is not an option.

In an exclusive interview with the MICHELIN Guide Digital, the 73-year-old French chef says: “Success is ephemeral, you need to reach out for it. I work hard every day to bring it out.”

Even though his fine-dining empire spans 13 locations worldwide, including Paris, Bangkok and Shanghai, he does not consider himself at the pinnacle of his career, adding: “I never think the work is done.”

Breaking Bread

Born in 1945 after World War II in Poitiers, France, Robuchon once thought of entering the service of God.

Those days, as Robuchon remembers, were “a period of restriction, when you didn’t have much to eat and parents said you should do that job because at least you will always have something to eat.”

And that was how this culinary giant found his way into gastronomy. He recollects: “When I was studying, the only moments of relaxation were when I went to the kitchen—that was like a holiday. I enjoyed [those moments] so much, but at that time, I was not allowed to do much, only peel vegetables.”

He also remembers to this day how his grandmother and mother cooked for the family as he was growing up.

“It was very personal and a symbol of love. After World War II, bread was always [baked] in big loaves, because you were not allowed to go to the baker many times. You had to keep your bread for a few days, sometimes a few weeks. That’s why they used to make big loaves of bread.

“We were Christians and a very special moment was at every dinner, [when] mother used to take a big loaf of bread and put it on her chest and do a cross on the bread. Then she would cut big slices to share with the family. It was really a matter of love and feeding your whole family. Cooking, passion and all the love was put into the cooking was shared with the family.”

He has expanded on this emotion ever since and carried it into the kitchen to mentor young chefs.

“Very often, when I see talent in a new chef working for us, I would ask him this question: ‘If you are cooking for your parents, loved one or friend, would you cook it the same way?’ I want my team and myself to cook as if we are cooking for family and very good friends. Of course it is important to have technique and quality, but if you don’t love the customer, you don’t make them happy. You have to put a part of yourself inside the cooking—that’s how a customer gets a very special experience.”

He laments that these days diners who eat out at restaurants may not know who made the dish, but he wants his DNA to shine through all of them.

His professionalism, rigor and creativity—and the high standards he sought—made him stand out, even as a young chef.

At the age of 29, he was already commanding and managing 90 cooks in the kitchen of the Concorde Lafayette hotel. He opened his first restaurant, Jamin, in Paris in December of 1981 and subsequently founded his eponymous restaurant, also in Paris, in 1994.

He recollects that when he began his professional career as a chef, cooking equipment was basic. But in the last 50 years, technology has changed the kitchen—processes are made easier and cooking has become a lot more technical than it used to be.

He finds even greater change on the produce front with the advent of technology and advancements in transportation. Good produce can now be found everywhere. Now, more than ever before, the role of the chef is to make the best use of such fresh high-quality produce, to bring out the essence and maximum flavor of the products.

In the last few years, he has noticed an emphasis on health and food. People want to eat good food but they want to eat healthy—and he is happy to oblige. He meets with health and nutrition experts all over the world, who give him advice on diet, products and techniques, which he adapts for use in the kitchen. In fact, he uses himself as a guinea pig. “Well, I will test it on myself to make sure it is true, that is what I have been doing. I am still eating a lot but following rules. So I have lost weight but I am feeling healthier,” he says, adding that he has overcome problems with cholesterol.

He has also been working with superfoods like turmeric and pomegranate for the past five to 10 years, testing their benefits before putting them on the menu. Ask him how to make the most of these superfoods and the chef in him shines through.

“I see it as a matter of how you cook. If you want to follow a diet for a long time, it must be good. In the morning, I often have avocados and tomatoes, but it can be boring to eat the same things every morning. But if you do it properly, like cutting the tomato the right way, not too thin or big, and seasoning it properly, that will make a whole lot of difference. Choosing the right kind of salt, such as fleur de sel which is crispy, having the right kind of pepper, grinding the pepper to the right size—all these details make a difference in the taste.”

Embracing Change

He lets on that he pays a lot of attention to what is going on, even if he doesn't say much about it.

“I listen a lot to what people feel, what people like and what they expect. I try to see what the next step is. The real challenge is to always feel what will be next and be ahead of the others. Not to follow but to be the person to find what people are expecting.”

He adds that when he was young, there were famous chefs like Escoffier, then the trends moved on to classical cooking, nouvelle cuisine and molecular gastronomy. Now, the emphasis is on health and organic foods.

“I am very interested in vegetarian food. People want to eat more vegetables, that’s the upcoming trend. It’s not even a trend, but a necessity of the future. And anyway, after a while, it will change again.”

So many changes have come and gone through the years, but this stalwart of the food industry is not one to be afraid of change. And he encourages chefs to embrace the new and to keep trying out new things.

Still passionate after decades in the kitchen, he says: “This is part of our profession. It’s a wonderful profession and you have so many things to try to change. Our profession is so wide and always allows us to create and to find new ideas and concepts.”

Ask him for words of wisdom for the younger generation and Robuchon, who was awarded the Meilleur Ouvrier de France, humbly says: “We have so many talents and so many passionate young chefs now. I hope these chefs do the cooking they love and not try to follow the trends. When there is a trend, all young chefs want to get into [it] but it is a choice that does not allow them to put their personality into food, so I believe they should [cook] the food they love and forget the trend.”

Giving Back

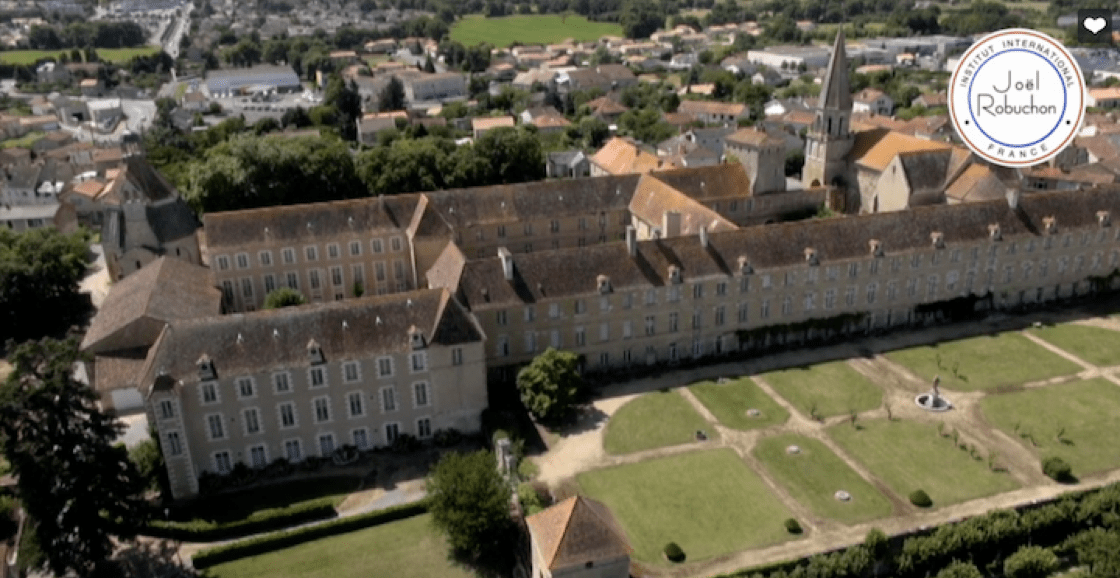

To nurture young talents, he recently partnered with a famous catering school in Lausanne to launch a cooking academy in the town of Montmorillon, near where he lives.

“There is a very famous proverb saying that goes something like this, ‘when an old man dies, a library burns down.’ I have seen so many good chefs—some famous, some not—who have gone and, with them, a part of knowledge and tradition is lost and nobody can take it back.”

Cooking has given Robuchon all he wanted, but what really matters now to him is passing on his knowledge to the next generation.

“I want to make this institute different from the traditional school because I have seen so many people disappointed by traditional ways of teaching. Some chefs come out of very good schools, but once they step into a restaurant, they cannot handle and quit. And this is such a waste, so I want to immerse people in reality and its expectations.

“I want them to have good theoretical knowledge and a strong foundation, so a high quality of transmission and technical know-how is important. When I started, I was training in the kitchen and did not learn in a school. But now, people go to school and do not face the real world enough.”

His ideal institute will receive 1,400 students in a very different way from that of the traditional school, planning to provide hands-on experiences for the younger generation—and there will be a hotel and restaurant in the complex. Students will train and work in different restaurants, starting from the canteen to gastronomic restaurants, to train in different sections, such as the bakery, patisserie and wine shop, in a professional environment.

Cooking What You Love

With all the knowledge he has been receiving all his life, Robuchon wants to transmit it before it gets too late. His plan is to achieve this by next year.

This passing on of knowledge began when he was 50, when he announced his retirement and began the popular cooking show Bon Appétit Bien Sûr, which presented simple and affordable recipes, and tips and tricks of the kitchen. This ran for a good 10 years.

Ask him what keeps him going, year after year, and the challenges he has faced, and he admits he has had tough times as well.

“Like everybody, I have had problems or moments that were difficult, but what motivates me is the opportunity to give pleasure to customers. Just seeing the customer happy makes me forget the challenges.”

One can expect at his new institute, that above and beyond the transmission of know-how and technicalities, young chefs will learn also about Robuchon’s philosophy and attitudes on cooking, for cooking is about sharing and an expression of love.

“I cook what I like. I will never cook something I do not like. If there is an element I cannot appreciate, I will not use that to make a recipe. So I only cook something with the elements I love. The only advice I can give, with a lot of humility, is do the cooking you love.”