If you look up at the walls of Sweet Home Café and view the extraordinary historical images that adorn them, your eyes will land on a quote from writer, cook and culinary historian Michael Twitty. It reads, "Our food is our flag . . . it sits at the intersection of the South, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America." This quote represents, in part, the monumental task being undertaken by the National Museum of African American History and Culture and its restaurant: to take an epic, complicated and often tragic history and let visitors touch it in a way that is both personal and immediate.

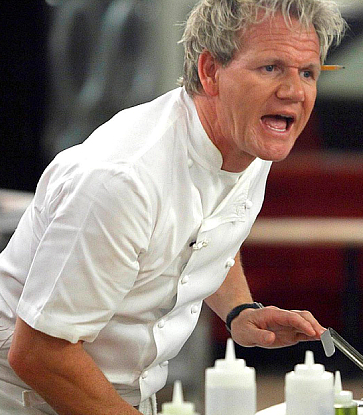

You'd be hard pressed to find a man better fit for this task than Sweet Home Café's executive chef, Jerome Grant. Originally from Fort Washington, Maryland, an area which hugs the Potomac river just south of Washington, D.C., Grant is the former executive chef of Mitsitam Native Foods Cafe, the restaurant housed in the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian. On a stretch of the National Mall where the best case scenario for dining was once a dirty water hot dog, Grant led a kitchen tasked with appropriately representing and making use of the culinary traditions and ingredients from five American Indian geographical regions.

Mitsitam was a proving ground for Grant, and an opportunity for him to show that he was capable of honoring history and culture while also serving food fit for today's museum visitors. The rotating, scratch-made menu featured creations like prawns with white asparagus and pink peppercorn sorrel butter, fresh walleye crisped in a cast-iron pan and whole braised pork shank with star anise. The food helped teach visitors about the experiences and history of a number of different American Indian tribes and cultures.

So it goes with Sweet Home Café, where the goal is to serve visitors while also teaching them about how African Americans fed themselves and contributed an untold amount to America's culinary history. "Sweet Home Café is like coming home," says Grant. "One should be able to sit at our tables, have a great meal and engage in conversation with people. For [the kitchen staff], we view food as a sense of community and understanding. At the same time, we're giving you that view through the African American eye."

As he walks through the kitchen and surveys the small army of cooks preparing food for the cafe's thousands of guests, Grant describes how the menu of the restaurant represents four geographical regions: The Creole Coast, The North States, The Agricultural South and The Western Range. In each, the history and experiences of African Americans are told through distinct dishes. "We've identified these four regions and it follows the migration of African Americans through the United States," Grant describes. "There's a lot of stories that we're telling. For us, we really want to push those stories."

The quest to find and develop recipes for Sweet Home Café wasn’t taken lightly. Exhibits dedicated to African American foodways are a part of the museum’s Cultural Expressions exhibit, and Grant says the initial recipe development was years in the making. Sweet Home Café, which is managed by Thompson Hospitality and Restaurant Associates, sent supervising chef Albert Lucas on a quest to help source recipes, while Smithsonian researchers also contributed. This included meeting with chefs like Charleston, South Carolina-based BJ Dennis, who is viewed as an authority on Gullah Geechee cuisine, which is a subset of Low Country cuisine native to the coastal areas from North Carolina to Florida.

A major feature of the restaurant is that the dishes being served are on the menu for a reason. Take for example The North States oyster pan roast, which honors Thomas Downing. Its origin, Grant says, is both unique and representative of how food and history go hand in hand. The son of freed slaves from Virginia, Downing migrated to New York and opened an oyster tavern that functioned as a stop on the underground railroad while simultaneously serving some of New York's most high profile white politicians and dignitaries. It's a dish that showcases not just the kitchen's cooking acumen, but also calls back to a man who survived and thrived during a time of great upheaval, and helped others to do the same.

These kinds of stories are common across the menu, and Grant enthusiastically describes a seasonal dish called son-of-a-gun stew, which comes from The Western Range station and will return to the restaurant's menu in the fall. "To me it is one of the more standout regions that we're focusing on, for the simple fact that once blacks were free, they went to the West to find new opportunities. A lot of those new opportunities started with chuck wagon cooking." While the stew originally was made with the less desirable parts of the cow—hearts, bellies, and the like—Grant describes the museum's incarnation as being "jazzed up" in that they use short rib instead of organ meat.

Even classic, more instantly recognizable dishes like fried chicken, shrimp and grits, collard greens and mac and cheese have their place on the menu. "You have The Agricultural South that has the comfort foods that we all know, that we all grew up loving," says Grant. But you'll also see foods that represent the diversity of different African American communities. "As you sit there and go through our stations, you'll see The Creole Coast [where] you'll see the hints of French-style techniques. You go into The North States and you'll see a lot more Caribbean aspects, as well as the West Indians and the Senegalese that migrated [there]."

The food at Sweet Home Café has been well-received, not just because of Grant's skills as a leader or a cook, or because of the obvious work his team puts into running the massive, 12,000-square-foot kitchen. It's also because the menu speaks to experiences that are personal and meaningful for both the kitchen staff and the museum's guests. Grant's own history informs his role. "My mother's Filipino, my father's Jamaican and my stepfather's a country boy from Hampton, Maryland. One day we ate boiled fish and rice and my stepfather taught me to make smothered pork, and then I spent my summers with my grandmother eating salt fish and plantains every morning. That's the great thing about African American culture—that we have so many subcultures that make us who we are."

Sweet Home Café has over 400 seats and serves thousands of people per day. The line can easily grow to be over an hour and a half long, and Grant says it's an opportunity to both feed people and teach them. "We have the little blurbs on the stations so people can read and understand. We have it on the signage waiting in the line. It is very important for people to understand what we're doing here. We don't want to just be dubbed as 'African Americans only eat soul food'—it's more than soul food, it is American food."

Photos by Jai Williams.