Bobby Pradachith is the 25-year-old chef and co-owner of Thip Khao. A glance at his Instagram feed reveals photos of his family and shots from his first trip to the ancestral family home of Laos. Those paying attention, though, will also catch a glimpse of not just upcoming specials, but of the type of food that makes Pradachith a standout in the generation of young chefs making a name for themselves—fresh and beautiful food that combines ancient flavors with modern plating and techniques.

There are a lot of reasons why Thip Khao is a remarkable restaurant serving world-class food. For one, the cuisine of Laos is a beautiful palette from which to draw flavors. Mountains of herbs and sliced chiles are a standard feature in Lao dishes, as is the joyful funk of fermented fish and meat. Fragrant soups, taught noodles and planks of crispy fried snakehead and catfish drizzled with pungent fish sauce don't hurt either. But Bobby Pradachith might be Thip Khao's true ace-in-the-hole and one of the big reasons it's held the Bib Gourmand designation for two consecutive years.

Thip Khao, the only Lao restaurant in Washington D.C., is a family affair. The restaurant is owned by Pradachith's father, Bounmy Khammanivanh, and his mother and co-chef Seng Luangrath, who left Laos with her family as a refugee in the years following the end of the Vietnam War.

Luangrath learned to cook both from her grandmother and from the elders in the refugee camps her family passed through before they ultimately arrived in California. Her home cooking became so legendary amongst her friends and the employees of her husband's construction company that she began catering. This led to the purchase of a Thai restaurant in Virginia called Bangkok Golden, which has since been renamed Padaek (the name of Laos' deeply funky, unfiltered fish sauce).

It was the purchase of Bangkok Golden that really changed things for the Pradachith. "It started a fire. My parents started a restaurant, [and] I wanted to open my own someday." Pradachith also credits high school vocational classes with helping prepare him for life as a chef. "I was very fortunate to go to a high school where we had a culinary arts program," where he would practice his knife skills, break down chickens and learn to bake bread.

After high school he enrolled at the Culinary Institute of America (CIA), where he earned both his associate and bachelor's degrees in culinary arts. While at the CIA he externed at the New York outpost of Buddakan and staged on both the East and West Coasts, all the while thinking about where and what he'd like to cook.

"I was in between wanting to cook Lao food and wanting to cook other food," Pradachith says. While the memory of his culinary heritage rested inside of him, he was drawn towards the precision, attention to detail and radical creativity of modern fine-dining restaurants—this created a problem.

According to Pradachith, his attending the CIA came with an understanding that he would return home to cook at Bangkok Golden, and his obligation was compounded when Thip Khao opened in 2014. For a young chef interested in developing skills in other kitchens—and maybe on another coastline—the pull toward home was bittersweet.

Thankfully, he was able to convince his parents that it was necessary for his culinary development to work in other restaurants, and he spent a summer working for Erik Bruner-Yang, a D.C. chef and now-prolific restaurateur who at the time was making waves with his ramen joint Toki Underground. In Bruner-Yang's kitchen part-time was Johnny Spero, a chef who Pradachith had wanted to work under for some time.

After returning to school he heard that Spero had taken a position at José Andrés' limited-seating, high-concept restaurant minibar. Pradachith says he sent over 20 emails to minibar asking if they might accept him for an externship, which didn't happen. However, a well-timed message to Spero in the months before his graduation netted Pradachith an invitation to stage during the 2014 Fourth of July weekend. The experience landed him a spot as a cook at minibar, where he worked for a year in the evenings while simultaneously cooking full-time at one of his parents' restaurants during the day.

Thip Khao is all the better for it. "There wasn't any Lao restaurant that I could go into in this country where I could learn about [Lao cuisine]," says Pradachith. "I wanted to work for these chefs and they have their styles, and it's definitely not Lao in any way, but it made me interested in implementing the styles I learned into the food I'm cooking now."

Now, he fuses modern techniques and sensibility with Lao flavors. He also strives to make his dishes look beautiful yet recognizable to the Lao people who come into his family's restaurants looking for a familiar taste of home. According to Pradachith, older Lao people have strong opinions about the way dishes should look and taste, and he says they'll tell him without hesitation if they think something has been prepared something. Combine this with the fact that he doesn't speak Lao (much to his chagrin), and Pradachith finds himself juggling creative freedom with seeking to appease and honor his culture.

An example of this is tam muk taeng, an upcoming special at Thip Khao. It's a common salad in Laos made from shaved and smashed cucumber and green mango with a sauce of padaek, tamarind, garlic and chiles. Pradachith has taken pains to make it look like it would if you ordered it in Laos, but he's made the dish his own with the addition of toasted black sesame seeds, toasted peanuts and grated dried scallops, which are salt-cured for five months, lightly smoked and then dehydrated, all in-house.

Likewise, an entirely off-menu experiment is his radical version of khao tom, a type of banana sticky rice. Pradachith's vision of this everyday dessert pairs banana ice cream with tamarind caramel, coconut-fermented honey mousse, puffed rice and salted citrus peel. His Instagram feed shows a few variations on ice cream and banana desserts, a flavor pairing common in Laos. His version, however, is a stunning departure, pairing these familiar flavors with modern techniques to make something reflective of his own culinary history, and where he hopes to go in the future.

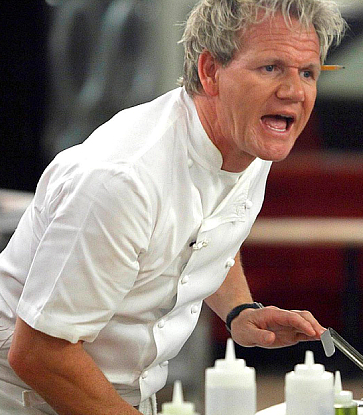

Photo of Bobby Pradachith by D.C. Central Kitchen.