To celebrate the Year of the Ox, Brandon Jew, chef-owner of One MICHELIN Star Mister Jiu's and bar manager Garrett Marks concocted a cocktail with Rémy Martin® XO and rice milk to celebrate the New Year. Read on for how Jiu celebrated Chinese New Year, how to make the cocktail, and for a preview of Mister Jiu's in Chinatown: Recipes and Stories from the Birthplace of Chinese American Food, his forthcoming book co-written with journalist and attorney Tienlon Ho.

Happy New Year! It's the Year of the Ox. What's your Chinese zodiac sign?

I'm a sheep, sometimes called a goat. I feel more superstitious as I get older. I’ve been thinking a lot about last year being Year of the Rat, and the traits of being scrappy and staying alive, and doing whatever is necessary. Coming into Year of the Ox, I've been feeling that there’s this reliability with the ox. There’s a lot of head down, just keep moving, maybe it’s slow but it’s very methodical and it’s going to get us to the end.

How did you celebrate Chinese New Year when you were growing up?

As a kid, I knew Chinese New Year was happening because I’d have a nice stack of red envelopes [hong bao or lai see]. I’d go visit my grandparents and their friends would be there and they’d pass out lai see and squeeze my cheeks really hard. We’d usually go out to dinner, which was a special occasion because we rarely went out to eat. We’d do the big banquet menu and take up three lazy Susan tables, including a kids' table, between the all the cousins, aunts, and uncles.

How we celebrate has evolved over time. We see less of the extended family now because my brother and sister have kids and a lot of cousins, and they’ve moved out of the Bay Area. These days I’m usually at the restaurant the entire two weeks [that span Lunar New Year] because we’re so busy. But when we do get to celebrate, I’ll drive to my parents' house and have hot pot, with a couple different broths going and vegetables and meat. I want to re-energize the family traditions and start to have more family get-togethers, maybe even at the restaurant on a day that we’re closed.

Food is a big part of the holiday, getting together with friends and family to eat. Although how we celebrate has changed over time, the food and the gathering have continued to be the centerpieces.

Tiger Milk Tea Punch

4oz jasmine rice milk (see below)

2oz Rémy Martin XO

1oz simple syrup (see below)

Combine all ingredients in a cocktail shaker. Dry shake and pour into cocktail glass filled with ice.

Rice Milk:

75g unsalted toasted peanuts

200g rice

16g jasmine tea (leaves)

8 cups filtered water

25g toasted sesame seeds

- Rinse rice thoroughly

- Steep jasmine tea in 8 cups of water for 3-5 mins. Strain and discard tea leaves.

- In a large mixing bowl, combine rice, sesame seeds, and peanuts. Pour jasmine tea over and let soak for at least 2 hours, overnight if possible.

- Add the ingredients to a blender and blend until smooth.

- Strain using a fine mesh strainer.

Simple Syrup:

1 cup filtered water

1 cup evaporated cane sugar

Photo by Colin Peck

And how did you celebrate this year?

There wasn’t the same kind of celebratory atmosphere we’re used to, especially in Chinatown, but I was determined to continue with traditions. We did some of the things we do every year: cleaning the house, filling the house with flowers and plants and repotting them, and we ate vegetarian the first day—a meal kit we were doing at Mister Jiu’s. Doing those things felt like some of the familiar traditions. The vegetarian meal kit included a citrus salad with an osthmanthus vinaigrette and watercress; our version of crossing the bridge noodles; some of the ferments we do here, like green garlic, braised peanuts that symbolize fertility, fermented mustard greens, and beans sprouts; moo shu mushrooms—lots of different kinds like maitake, shiitake, and king trumpets—with burdock, jicama, egg, celery, and pancakes and a peanut-butter hoisin. The final dish was a smoked tofu dish, more Hunan style, a little spicy, with peppers, chili and leeks. Dessert was an eight treasure rice pudding with longan, lotus seed, passionfruit, vanilla, and pomelo.

It’s such a festive time, and normally we're hosting celebrations in the dining room, but we still felt good about helping people celebrate the new year with these meal kits. It’s comforting how many people are celebrating Lunar New Year across so many countries.

Usually at the end of Chinese New Year, Chinatown has this huge festival, and there’s a parade. The most exciting thing we did [this year] was light off a bunch of fireworks. Every day here in Chinatown, you’ll hear someone light off a good round of fireworks. I hadn’t really thought about the meaning of fireworks, but they're meant to ward off bad spirits and energy. That feels more meaningful this year.

Tell us about your Chinese New Year cocktail, Tiger Milk Tea Punch.

My bar manager Garrett Marks and I started by making rice milk fortified with sesame seeds and peanuts and used that as the richness we were looking to add to the cocktail. I was really happy with how it tasted. It’s pretty simple once you make the rice milk, which is so good you can drink it on its own, but when you add XO to it, wow, it was like a lactose-free White Russian. The complexity really comes from the sesame and peanut, how they match with the cognac. It’s really a nice pairing.

To eat, ham sui gok is really taste with brown liquor cocktails. The glutinous rice wrapper on the outside is nice and chewy, and then you get to the center and it’s just this super rich pork, mushroom, and jicama. It’s one of my favorite things to have with a cocktail. Cocktails are balanced in a way that’s not exactly like a wine pairing, where you’re looking to either complement or contrast the wine. Cocktails usually have so much going on, it’s hard to pair anything with them, but I’d gravitate towards ham sui gok.

With a boozier cocktail like Tiger Milk Tea Punch, you want something that brings out the caramel notes in the Rémy Martin XO cognac. It easily pairs with dessert, so for me that's the nian gao. It’s so ubiquitous with Lunar New Year, and it's a nice bite to eat alongside the cocktail.

Nián gāo (黏糕, in Mandarin) are the fruitcake of Chinese desserts. The difference is that they’re steamed, not baked, and made of glutinous rice flour instead of wheat flour. But like fruitcake, they show up (sometimes inconveniently) on major holidays. Nián gāo means “sticky cake” and is also a pun for “a year better than the last,” so around the new year, you make it to bribe the Kitchen God and glue his mouth shut, as he’s to report on everything he’s overheard in your kitchen the past year. That classic texture can be polarizing for people who are unfamiliar with it, so for this version, I looked toward butter mochi, a favorite from the 1970s era of Oriental-style convenience baking. Baking turns nián gāo into a cake of wonderful contrasts—still chewy but topped with a golden crust. Winter is peak nián gāo season, so I use brandied cherries, like Luxardo, but feel free to use other dried fruit; rehydrate for fifteen minutes in some hot water, rum, or brandy, then chop into ½-inch pieces so they stay evenly distributed throughout the cake.

Active Time — 20 minutes

Plan Ahead — You’ll need about 1 hour for baking

Makes 12 to 16 servings

Special Equipment — 9 x 13-inch baking pan (preferably metal)

½ cup / 110g unsalted butter

2½ cups / 590ml whole milk, at room temperature

½ vanilla bean, split lengthwise, seeds scraped, and pod discarded

3 eggs, at room temperature

1 lb / 450g short-grain glutinous rice flour (such as mochiko)

1 cup / 200g granulated sugar

1 Tbsp baking powder

1 pinch kosher salt

½ cup / 90g drained, pitted Luxardo cherries, or rehydrated dried fruit, drained and coarsely chopped

- Powdered sugar for dusting, or clarified butter for toasting (optional)

- Preheat the oven to 350ºF. Line the bottom of a 9 x 13-inch baking pan with parchment paper.

- In a large saucepan over low heat, melt the butter. Remove from the heat. Whisk in the milk and vanilla seeds until combined, then whisk in the eggs until smooth.

- In a large bowl, whisk together the rice flour, sugar, baking powder, and salt. Pour in the milk mixture and whisk until smooth. Stir in the cherries, then pour into the prepared baking pan.

- Bake the nián gāo until light golden brown and a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean, 55 to 60 minutes. Let cool until warm, about 1 hour. Remove the nián gāo from the pan, peel off the parchment, dust with powdered sugar, and cut into squares to serve. Or skip the sugar dusting and toast the slices in a pan on the stove top with clarified butter until crisp before serving.

Reprinted with permission from Mister Jiu's in Chinatown: Recipes and Stories from the Birthplace of Chinese American Food by Brandon Jew and Tienlon Ho, copyright © 2021. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

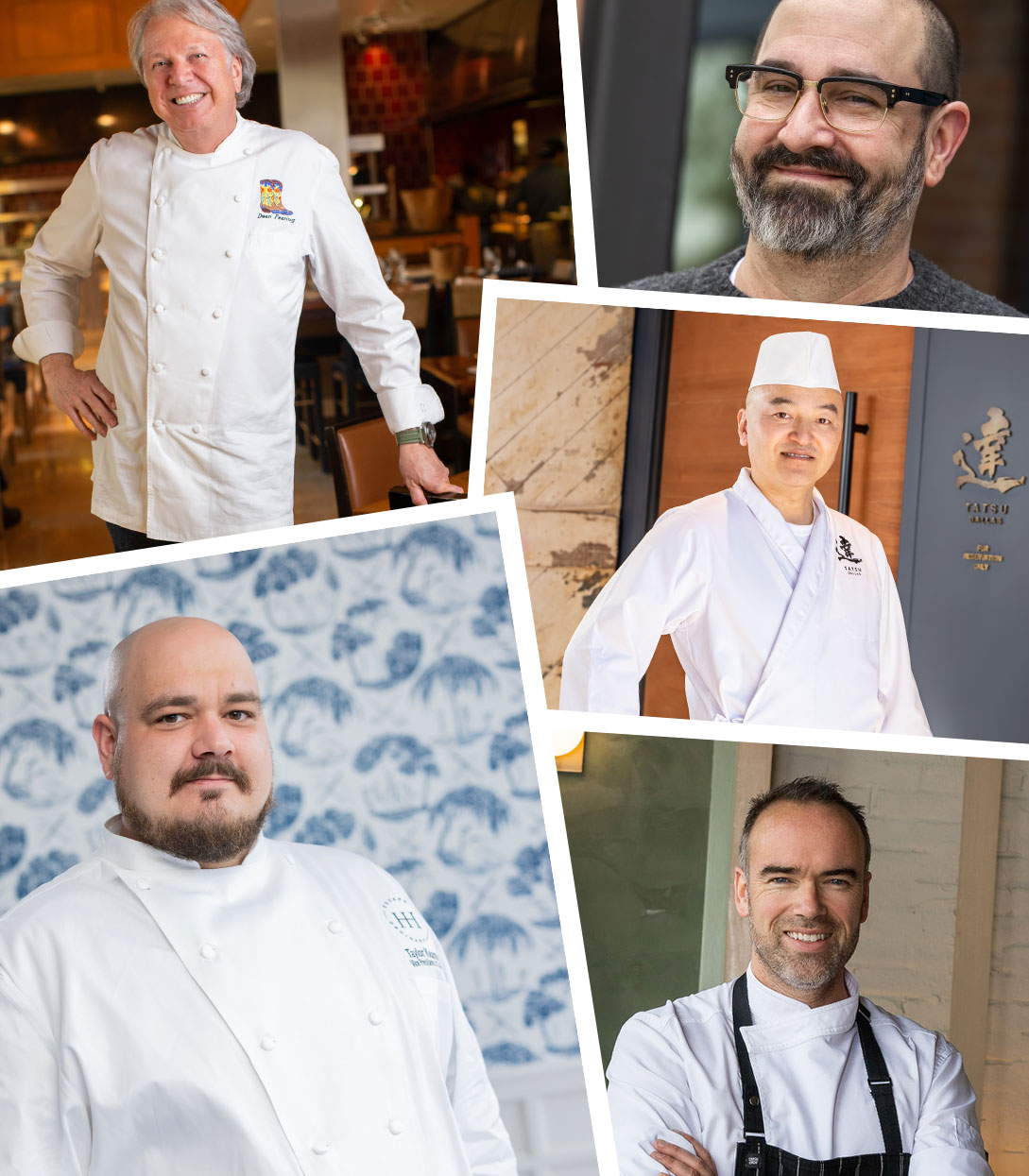

Hero image: Mister Jiu's chef-owner Brandon Jew. Photo by Colin Peck