Saltiness, umami and sourness are the defining flavours of traditional Chinese fare, so how did spicy dishes such as water-boiled fish, spicy hot pot and Chongqing noodles (xiaomian) become some of the biggest icons of modern Chinese cuisine? How did the chilli, which only made its way to Asia 400 odd years ago, become such a popular seasoning?

There is so much to love about chillies. Beyond their fiery flavours and the wonderful dishes in which they star, there are also fascinating stories, history and collective memories behind these heat-generating berry-fruits. Let’s take a look at how chilli peppers have become a universal language that connects modern gourmets and chefs, starting in South America.

For many Latin Americans, their first encounter with spiciness is the chipotle candy they eat as a child. Ricardo Chaneton, Venezuelan native and chef-owner of MICHELIN-one-starred Mono, recalls his childhood memories laced with piquant flavours. Chillies are the backbone ingredient in Latin American cooking, especially Mexican. Known worldwide for their love of chilli peppers, Mexicans add chillies to everything: from candies and salsa to meat, desserts and even beer.

While Mexico is home to many varieties of chillies with different sizes, colours, aromas and levels of pungency—all thanks to the diverse climate and terrains of the Caribbean; chilli peppers actually originated in Bolivia. Knowing that his customers may not be familiar with the hot chilli, Ricardo created the “MONOpedia”, a little blue book offering details and explanations about the chillies from Mexico, Peru, Brazil and beyond that are used at Mono. This way, customers will be able to enjoy these fiery treats with more knowledge and appreciation of what’s on their plates.

Ricardo is intrigued by how much respect have been shown to chillies in South America since ancient times. “There’s one name for fresh chillies, and another name for them if they’ve been air-dried. There’s a rigorous classification system.” For instance, part of the “Holy Trinity” of Mexican dried chillies, the ancho chilli—often used to make Mexican mole—is known as poblano chilli when it is fresh. How do locals differentiate and remember all these names? As it turns out, chillies are named according their characteristics, such as shape, width, pattern and even sound. Ancho means “wide” in Spanish, which also describes the ancho chilli’s unique wide and flat appearance; aji amarillo, a chilli pepper of Peruvian origin used to make Spanish sofrito, is named after its yellow skin.

Ricardo’s open kitchen currently displays over 10 different dried and fresh chillies, but it hasn’t been easy sourcing them due to the low demand in Hong Kong’s F&B industry. He recalls many suppliers’ initial reluctance to import the chillies, and it wasn’t until his restaurant gradually gained recognition that his chilli collection began to grow.

RELATED: Ricardo Chaneton On His "Destiny" To Open Mono In Hong Kong

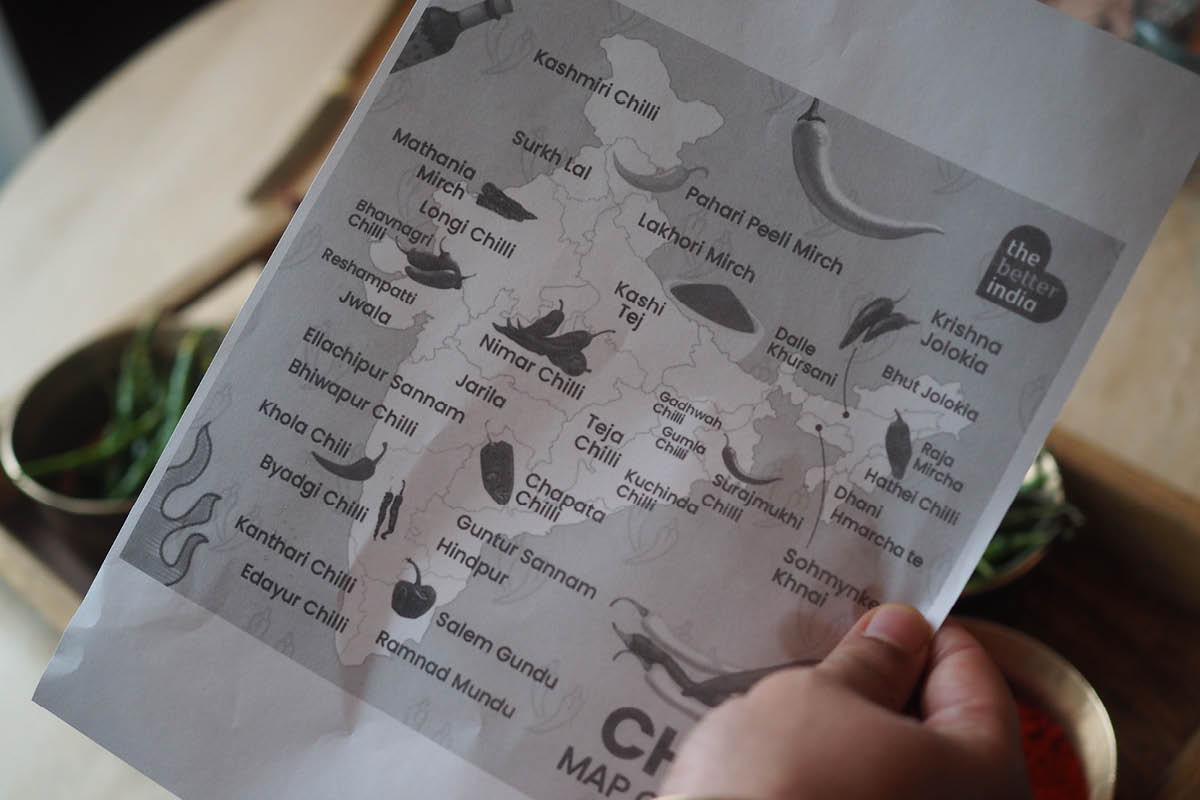

Coincidentally, MICHELIN-one-starred restaurant Chaat also houses a mini display of chillies.

For Indians, spiciness is a reflection of their diverse culture. Over 450 years ago, chillies made its way from South America to Europe and Asia following the voyage of Christopher Columbus. India has since become the global distribution point for chilli peppers. Today, over 200 chilli varieties are grown throughout the country, and these hot peppers are woven into the cultural fabric of India. “Just like green chillies, some people eat them raw and fresh as a remedy to beat the summer heat; others make nimbu mirchi using seven green chillies and a lemon and hang them up to ward off evil,” says Manav Tuli, the Indian chef de cuisine of Chaat. He points out that the ghost pepper (bhut jolokia) produced in north-eastern India is one of the hottest chilli peppers in the world, and that the kashmiri chilli may be native to India (“though this is a controversial subject in the country”).

(Pictured left: Pork cheek vindaloo is the spiciest dish on the menu. Manav says that this is a classic curry dish with Spanish influences.)

In India, chillies are eaten raw, pickled, or ground into powder and mixed with numerous spices to create masala for making curries. “This is a delicacy enjoyed by both emperors and commoners alike!” Manav remarks. At Chaat, diners can find the very spicy vindaloo, the mild British-style Railway lamb curry, and the chef’s signature burnt chilli chicken tikka, which has been sprinkled with chilli flakes to stimulate the palate. Maintaining control and consistency for each curry dish is no easy feat. “The tens of chillies and spices each have their own optimal timing to be added to the pot.” Being able to teach the kitchen staff how to get the timing and heat right is something Manav is very proud of.

(Pictured right: Manav’s signature burnt chilli chicken tikka)

Chillies made its way to India during the Age of Exploration, and landed in China around the tail end of Ming Dynasty and the start of Qing Dynasty. According to records from Qian Nan Shi Lue written during Qianlong’s rule in the Qing Dynasty, chillies were once known as “sea peppers”, a name signifying its foreign origins. In China, chillies were first eaten in Guizhou. Published during the Kangxi period, Qianshu has written the following about chillies: “when there is a shortage of salt, chilli peppers are used as substitutes. The peppers are naturally pungent, and this pungency can replace saltiness.” At first, chillies were seen as a salt replacement, but as they became more common in different parts of China, chillies were made into different condiments. Examples include Sichuan’s Pidu chilli bean paste and Guangdong’s Jieyang chilli paste, which are predominantly salty with spicy kicks.

To the Chinese, “spiciness can be a delicate and complex flavour with depth, just like this emerald-green Yunnan wrinkly pepper,” describes Nansen Lai, owner of Jing Alley, a MICHELIN-recommended Sichuan restaurant in Hong Kong. Most Sichuan Jianghu dishes use erjingtiao chillies and millet peppers together with Sichuan peppercorns, ginger and garlic. These ingredients with intense flavours pack a punch to the taste buds and leave a lasting impression. Though when spicy dishes fall into the hands of skilled Hong Kong chefs, they may also evolve and be elevated in different ways.

Unlike the usual Sichuanese fare that go heavy on the mala spiciness, heat and oil, the creations at Jing Alley, such as its Chengdu-style water-boiled fish and water-boiled duck’s blood with beef, are unique in their own ways. The latter uses not only Chinese peppercorns, but also dried green chillies from North Korea and Thai green chillies to give the dish a gentler flavour that can highlight the seafood’s umami. This may not be the traditional, authentic cooking method, but is no doubt a show of Sichuan cuisine’s appeal and the true meaning of “100 dishes will have 100 flavours” (a common saying about Sichuan cuisine).

(Pictured left: Nansen Lai, owner of Jing Alley)

Chipotle candy, curry and water-boiled fish… who knew these dishes can teach us so much about different cultures?

CONTINUE READING: Let's Chaat: The MICHELIN Guide To Indian Street Food

Photos and text by 孔牧, translated by Iris Wong. Read original article here.