On the other side, the same scene unfolds at the zi char stall. Only, instead of mee hoon goreng, the hawker is infusing crab bee hoon with a good hit of wok hei. This dish is set to send oodles of pleasure to those slurping it up in the next few moments.

Such is the versatility of this noodle - rice vermicelli. Indeed, it isn’t much of a stretch to say that the story of the thin white noodles is also the story of our nation; of how the humble bee hoon left the shores of China, reached the southern tip of the Malay peninsula and is now tossed into sizzling hawker pans serving up everything from Malay to Indian food.

Bee hoon isn’t the only one, in fact, there are dozens more found in the many cuisines that this city has to offer. Here’s eight of them.

These flat and wide strips of rice noodles are most commonly enjoyed as char kway teow – a national favourite where they’re tossed in a searing hot wok with a variety of sauces, lap cheong (Chinese sausage), bean sprouts and cockles. While they’re widely seen as noodles thanks to its long strands, it’s made more like a rice cake – by steaming the batter which is made from a mix of rice flour, wheat starch flour, salt, oil and water – in a thin layer in a pan. Once it’s set, it is removed and then cut into wide strips.

When it comes to the history of Singapore’s food, ban mian, or handmade noodles are a fairly recent introduction into Singapore’s hawker scene. Its ingredients are basic: flour, eggs, water and salt kneaded together to develop the gluten for a chewy texture. Traditionally, these noodles are sliced by hand but many today prefer to use a pasta roller for its speed and ease of churning out the noodles quickly. They are then cooked in a broth typically made from anchovies with some greens, an egg and minced pork.

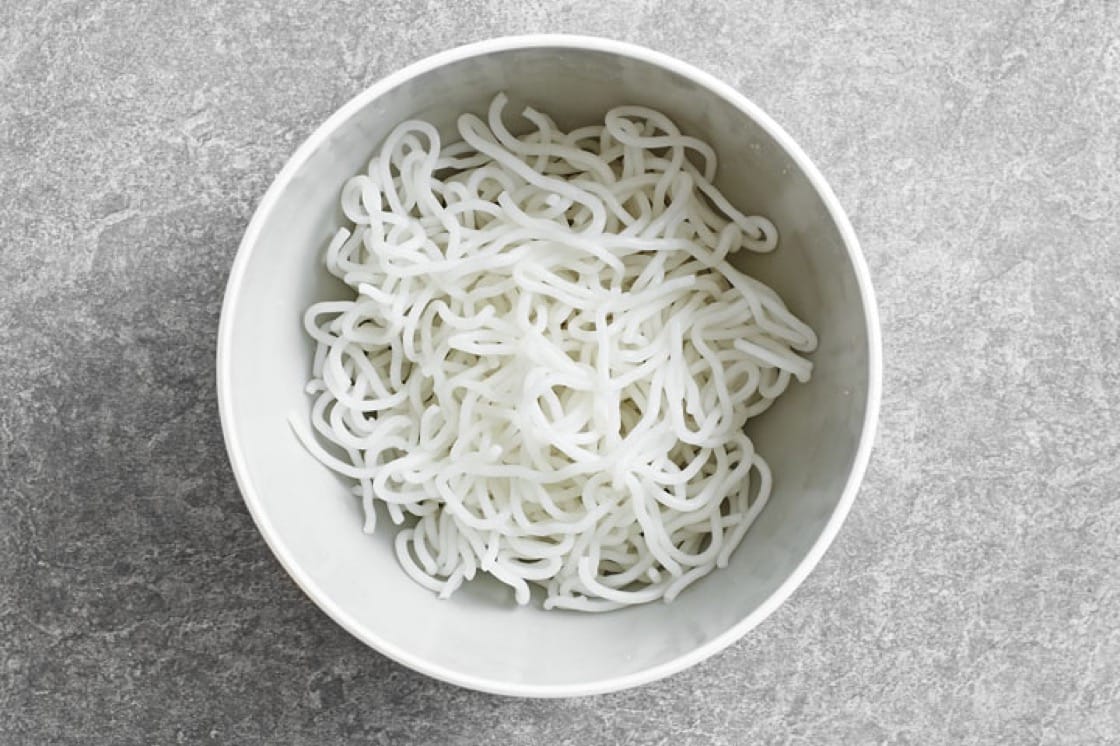

These short strands of noodles are made from a combination of water, glutinous rice flour, rice flour and sometimes corn starch to reduce breakage while cooking. Once mixed, it is pushed through a noodle press and into boiling water. At home, it can be enjoyed as a quick stir-fry, while some hawkers will peddle these as part of their selection so customers can choose their favourite to be used in dishes that vary from fishball noodles to bak chor mee.

These ubiquitous noodles are enjoyed in many forms, from prawn mee (noodles in a prawn-based broth), to Indian- style mee goreng and in mee soto (noodles in a spiced chicken broth). Most commercial versions available in the supermarket are made of wheat flour, soya bean oil and food colouring though some brands have begun introducing wholemeal versions for those looking to increase the nutritional profile of this staple.

These noodles are so closely associated with Singapore’s version of laksa, that few other types of dishes are made with them. In Bib Gourmand recipient 328 Katong Laksa, the noodles are cut into shorter lengths so it can be eaten with just a spoon. Like bee hoon, they are typically made of rice flour and parsed through a noodle press into boiling water, though laksa noodles are usually sold fresh and not dried.

Mee sua and bee hoon may look alike but their textures and flavours are entirely different. While both are made with rice flour and sold dry (soaking them in warm water will rehydrate the noodles), mee sua tends to contain a touch more salt with some recipes even calling for additional mung bean flour. Dish-wise, it is best known as a Chinese New Year speciality for the Hokkien community where it is served in a thin broth with two hard boiled eggs meant to symbolise prosperity and longevity.

When Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle received its Michelin star in the debut of Singapore’s MICHELIN guide, it propelled the humble bak chor mee into dizzying heights. The noodles it uses? Mee pok – flat egg noodles cooked till al dente. The same noodles are also used to make fishball mee pok and are a common dish across the island’s hawker centres and food courts. Both dishes come in the soup and dry version where the former is steeped in a broth while the latter is generously doused in a variety of sauces and sambal.

These thin noodles made of rice flour are often sold dry and rehydrated by soaking in warm water. It’s as ubiquitous as the yellow noodles and has been used across the colourful spectrum of Singapore’s culinary offerings. For bee hoon with a difference though, look to one-Michelin-starred restaurant Putien which serves up a thinner version handmade in Putian, China. The thin white noodles are dried manually under the gentle sun at the crack of dawn, instead of by machine as is the case with commercially-available varieties. This gives the bee hoon at Putien their edge, as the texture turns out silky smooth.

Recommended reading: View more stories on hawkers here