Ask Alain Passard if he is afraid of anything — to lose the three Michelin stars his restaurant L’Arpège has garnered over the years, perhaps — and his eyes light up as he says: “The only thing left to do when you are afraid to take risks is nothing.”

The risk-taking chef knows what he is talking about. Most famously, in 2001, he struck off the menu the meat dishes which had won his restaurant the coveted stars and switched to exploring plant-based cuisine.

At that time, his announcement sent shock waves throughout the gastronomic world. He was so ahead of his time that his radical change “was completely misunderstood by many chefs who still ask themselves today what really happened to me. Let’s say many peers did not see this with a very keen eye.”

But he knew what he was doing and made his choice.

“I had almost decided to change profession,” he says with a laugh. “Cooking vegetables is another job; it reminds me of painting or tailoring.”

Conscious Shift

With child-like eyes that twinkle with delight and add emphasis to his words, Passard explains: “The shift that occurred to me from handling animal texture to vegetal texture in my cooking was caused because I had reached the limits of what I could achieve with animal texture. My hands wanted to explore new sensations on vegetable textures. I wanted new flavours, new scents, new images, new sounds.”

Even today, his desire for change is palpable when he speaks about it.

But that desire to switch from meat to plants required an incredible amount of work on his part.

“When you go from the rib eye to a carrot salad, the carrots need to be exceptional. I worked day and night to figure out this vegetable-based cuisine and bring it to a gastronomic level.”

At the time, there were voices of dissent which discounted this move. But Passard says firmly that everything he did came from his “heart and passion” for his work and there was no marketing plan behind it.

“It was the path of a cook who wanted to move on to another cooking book, a cook whose hand was tired of the animal texture and wanted to explore a new space.”

Looking back, Passard is extremely proud of what he has achieved, especially his gardens in Sarthe, Eure and Manche, which are of three distinct terroirs for the planting of different vegetables.

“My gardens and my orchards give me immense pride. There is not a restaurant in the world like us that is completely self-sufficient for its vegetable supply. We have 10 hectares of vegetable farming, 12 gardeners and this year we will produce more than 50 tons of vegetables. Organic, no chemicals, no pesticides. Every morning, vegetables are harvested and reach us at the restaurant for lunch and dinner preparation.”

“Today, almost 20 years later, a lot has changed. All chefs have improved their menus with vegetable dishes. In France many chefs have a small garden, maybe not very big, a plot, where they can grow their own vegetable. This is a story that triggered and opened the door to vegetable cuisine, which now has its own place, just like fish cuisine, meat cuisine — it has its right to exist.”

Beaming, he quips: “No point being pretentious about it, but I am very proud of this decision I made almost 20 years ago that opened the door for a carrot, a turnip, a leek, to be cooked in an artistic and gastronomic way.”

It is also no mean feat that the restaurant has managed to retain its three stars up till this very day.

Although L’Arpège now does serve meat, it is still renowned for its vegetables. The chef’s eyes shine as he says: “I like the idea of pushing your work further on a turnip than on a chicken. That’s why I said I almost changed profession — cooking vegetables requires a lot of precision, attention and finesse, you must have a light hand.”

On a deeper level, he says working with vegetables made him realise that cooking meat brought out aggression in him.

“Why? I do not know. Is it because of the relation to a dead animal, to blood? What’s for sure is that when I shifted to vegetable cuisine, I entered a very smooth space. I felt calmer and more serene.”

You can say that he has experienced two radically different lives as a chef — one that worked on meat and another on vegetables — and appreciates the creative processes of both.

The artistic family Passard was raised in honed his love for the arts, music and, on a broader level, creation.

“My father was a musician, my grandmother was a cook, my mother was a tailor and my grandfather was a sculptor. Creativity was the link to everything. My brother and I were dressed from head to toe by our mother who would tell us about the quality of the fabrics. On the kitchen table, there would be her sewing patterns, scissors and chalk,” he recalls.

“My father was a clarinet and saxophone player, and also a drummer. Creation was in the air to hear and touch. My grandfather would work on wood, rattan. He was doing wicker work and he would also work on blocks of wood and carve figurines. My grandmother was a very good cook, she would prepare terrines and roasts which at the time was cooked on a wood stove. Everything we had on the plate was really crafted. It was a very artistic surrounding. It makes a mark on you.”

He decided at age 14 that he would immerse himself in the field of culinary arts and, to this day, he says this is the best decision he has made.

“I never regretted it. Every day is like a first day. We are artisans and we have an incredible job. Very few jobs allow you to activate your five senses. It is a stimulating job that makes you feel good. Great cooking today is more of an adventure than just a job.”

He likens the work of a chef to that of work done by great painters, musicians, writers, dancers and sculptors.

“We do this job because we have passion for it and because we love it, and it is gratifying to the five senses. I like to be puzzled by a scent, a flavour, the sight of something in the garden, for instance, the sound of fire on the stove, the sound of cooking. A tomato and a celery do not make the same sound during cooking. Finally comes the hand, the gesture, that is able to craft something completely new. We are able to nourish our five senses through this creative process.”

Just as he is demanding of the produce he uses, he is also particular about the food he eats. He eats food that is mostly vegetable based but not exclusively. In fact, he loves to eat anything that has a history.

“I would eat a nice poultry, a lamb from the Mont-Saint-Michel. Behind every of these products, there is a craft, a person, a poultry or lamb farmer, or a vegetable farmer. Everything on the table at L’Arpège has a history: the history of the bread comes from the flour, the history of the butter from the cream. Each product has a passport, an identity, a provenance and a know-how behind it.”

He is equally passionate and emotional about the space L’Arpège has occupied since its opening more than 30 years ago.

“There is a great story about this place and me because this is where I learnt to cook in the 70s. There was a great chef called Alain Senderens and the restaurant then called L’Arquestrate received three stars in 1978. I worked for three years with him, then I left to work with other chefs. Then in 1986, when I set up my restaurant, I took the place of my mentor who had left for Lucas Carton Place de la Madeleine. In the end, I had the chance to take over the place that had belonged to my mentor, the place where I learnt to cook, this is a very strong feeling.” He adds: “It is important to feel good in a place.”

Unlike other chefs who aspire to build their brand, Passard made a decision early in his career to have one address, one restaurant — and that he would be there to cook every day, with his hands in the pots.

“This energy is focused in one place where I love to be, with my team.”

Passard has been an important mentor and a great inspiration to many young chefs. When asked what the most difficult thing to teach is, he pauses before replying: “Nuance is the hardest thing to teach. It is like tempo music, like learning how to make a pause in a recipe — that’s the most difficult.”

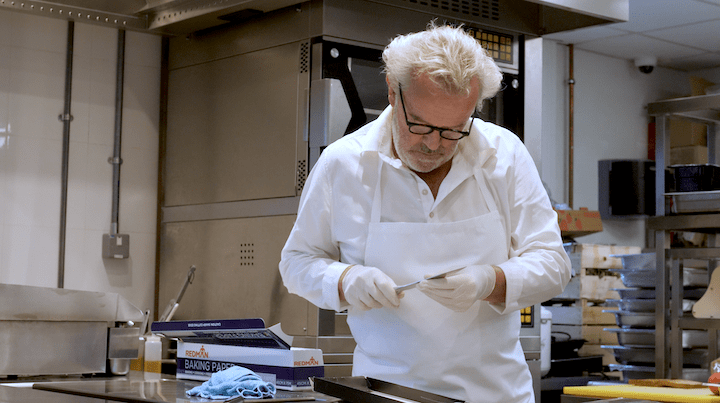

After a slight pause, he adds: “Everything I have achieved today comes from my 10 fingers, from my hand at work every day. I think my hands are the most precious thing I have besides sight. That’s what I want to teach to all my chef students — the gesture, the grace, the agility of the hand, the dexterity of the hand.”

For a chef like him who has changed times, Passard says he is sometimes still trying to make sense of the shift he initiated 20 years back: “You could say that 20 years later, I still cannot explain all of what happened. Of course I was needing a change, then there were events like the mad cow disease, but there is more to it. And 20 years later, I am still searching. I like to talk about it because it forces me to dig inside and connect the dots.”