As one of the eight primary Chinese cuisines, Cantonese food highlights the freshness and the original taste of the ingredients, with various cooking techniques involved. With a spatula and a pen on hand respectively, both the chefs and gourmands contribute to the eminence of the cuisine. In this series of eight stories, we tell the tales of the most celebrated figures in the Cantonese gastronomic world and the unforgettable episodes in its history.

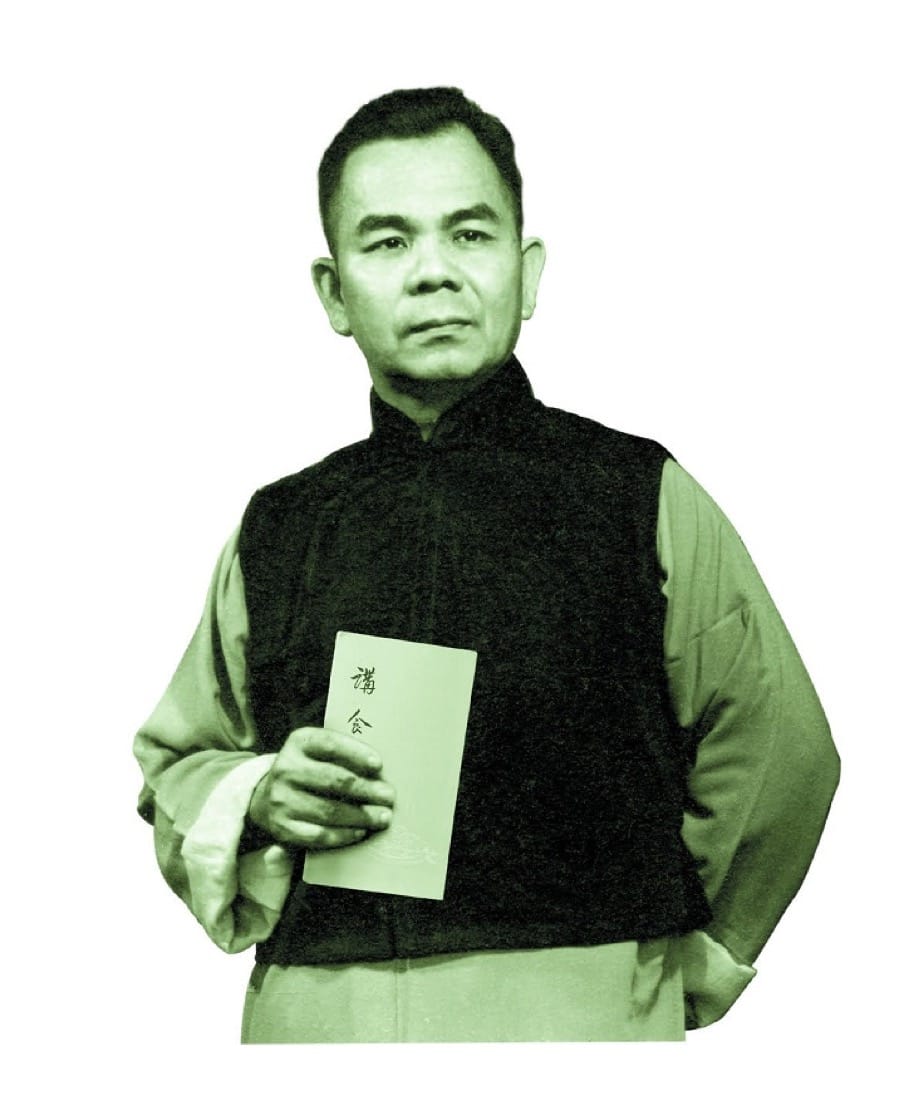

You can perhaps call Chan Mong Yan one of Hong Kong’s first food writers. Long before the Internet was even born, the Hong Konger was already writing a food column in Sing Tao Daily, where he was the editor-in-chief. He published about 10 hugely influential books, and opened the door for other food writers in the city to follow in his footsteps.

One of his daughters-in-law, multimedia journalist and author Sonia Ng, took on the task to collate a 300,000-word draft written by Chan and sent it to the Commercial Press for republication in 2007. The result is the five-volume Food Classics (《食經》) , a highly admired work of food literature.

Food Classics was followed by three volumes of The Way Of Eating(《食之道》) . While the former introduces the principles, concepts and cultural background behind different dishes, the latter is a detailed account about the origins and transformations of Cantonese, Teochew, Shunde and Hakka cuisines. Both works are highly informative and regarded as a valuable reference for many Cantonese chefs, leaving lasting influences on the development of the cuisine.

Before Chan, food writing in Hong Kong was limited to recipes. His columns took readers out of the kitchen to record food-related history, customs and social changes. This not only turned food into a subject of literary value, it also gives gastronomy a sense of depth. If Hong Kong food culture exists, Chan is the founder of it.

“He is very compassionate towards the public and I am deeply touched by it,” said Ng in an interview with Apple Daily newspaper in 2008, as she was promoting Food Classics. “The

entertainment scene of the 1950s wasn’t as developed as it is today. Chan Mong Yan shouldered the responsibility to explore the wet market and taste food at restaurants every day in his cheongsam. Food writing only took off gradually after that.”

“The post-war period was different from now. Few families could afford to have a meal at a restaurant or buy fine ingredients. Therefore, he spent a long time at the market, so he could talk about the food prices and his observations in his articles, and at the same time taught the readers to make good dishes with simple ingredients. He also published many letters from the readers. As you are reading this book, you will find out a lot about the old Hong Kong.”

Expanding One's Horizons

To call oneself a gourmand, one must possess an understanding to social life and cultivate a sense of connoisseurship of the palate. In the modern age when food information can be obtained easily from the Internet, it is not hard to become a gourmand or food blogger.

But in the 1930s, Chan built a foundation for his food literature through his identity as a journalist. His travels encompassed various regions of China, from which he accumulated culinary knowledge and all the human practices related to it.

Diora Fong, a food writer who is married to Chan’s second son Chan Kei Lum, added: “He loved eating and was extremely curious. When he came across something delicious, he would go to the trouble to ask for more details about it. Further to that, he had the habit of keeping a journal through his profession. Little by little, he formed an opinion and understanding about food.

“Another crucial fact was that he enjoyed helping others and made a lot of connections because of that. As a journalist, he also knew many important figures. Wherever he went, someone would treat him to a good meal. Therefore, he had tried the food of the people and had attended the banquets of high society. All of these provided the right conditions for him to become a gourmand.”

Fong added her observations of her late father-in-law: “He knew the ways of eating very well, but he wouldn’t try to be picky to show off his taste, and he never criticised someone else’s dishes openly. His principle was: ‘Unless I could do it just as well or offer an advice to improve it, I don’t have a right to criticise’.”

The standards he set for himself probably seem archaic in this modern age of online food reviews, where getting more eyeballs is deemed to be of utmost importance.

Garage Stuffed With Bags Of Dried Seafood

Even though he loved eating and was a connoisseur, Chan did not let it take over all his life.

Chan Kei Lum spoke fondly of his father, saying: “If he had a $100, he would spend $90 or even all of it to help others. He would never use that $90 for food. What he pursued was the symbolic value of the dishes, not the prestige. He never overindulged himself.”

In fact, the legendary food writer did not have a large appetite, never eating more than what he could manage.

“My father’s daily diet was very simple: rice, soup, vegetable, meat, a small portion of everything. He also ate moderately at dinner parties.”

After retirement, Chan Mong Yan emigrated to the United States. Among all his offspring, Chan Kei Lum lived the closest to him. In a way, that turned him and his wife into competent cooks. During the week, there would be at least one or two days when Chan Mong Yan hosted dinners at home for the slew of friends he had made. Playing the role of an advisor, he would draft a menu and let his son and daughter-in-law execute the plan, giving them suggestions on the sideline.

“He paid so much attention to the detail. Even the serving ware was chosen carefully to match the dishes. For example, dark green vegetables were served on white plates, while light green vegetables should go with black plates,” Chan Kei Lum noted. Even though the bowls and plates they used were antique fine porcelain, “he wasn’t obsessed with things like that. He wouldn’t get upset when something was broken”.

Every guest that made it to the dining table of Chan’s home was a prolific name. The list included military general Zhang Fakui and painter Zhang Daqian. His son recalled with great humour how the air in California, where they had settled, was dry and extremely suitable for preserving dried seafood: “The garage of our home in California wasn’t for cars. It was stuffed with bags of dried seafood, just like shops that sell these ingredients. It was spectacular.”

A Strict Teacher

Chan Kei Lum and his wife, the “family cooks” of the Chan household, held onto their positions for 20 years. During this time, they also witnessed Chan Mong Yan giving cooking lessons to Pearl Kong Chen, who is herself a descendant of the greatest gourmand in Guangzhou.

Chen’s grandfather is an incredible gourmand from Guangzhou called Jiang Kong Yin (also known as Jiang Taishi). Nevertheless, she had never worn an apron before the age of 40, when she wanted to recreate the dishes from her grandfather’s times for her ill mother. “Father-in-law did the talking and Pearl did that cooking. He was very tough on her,” the couple noted at the same time.

“There was a memorable event, when Pearl prepared a whole table of food, but she used the same ingredient three times — not sure if it was snap peas or fava beans — and he scolded her sternly, saying this was not up to the standard; the same ingredient should only appear twice at most. Pearl ended up in tears and we could only sit still there.”

In other interviews, Chen had also mentioned that Chan Mong Yan not hold back from critiquing her cooking in public.

A decade ago, a publisher asked Chan Kei Lum and Fong to write recipes based on the books of Chan Mong Yan. In his writings, instead of telling readers how much salt and sugar to add, he had explained why salt and sugar are needed, and other cooking concepts.

“We had never thought that those 20 years of being ‘family cooks’ would bring us new opportunities in the later stage of our lives,” said the couple.

Under the name “The Chans' Kitchen”, they published the first recipe book, Hong Kong Cuisine Classics, which met with rave reviews.

Immediately after that, they wrote Hong Kong Cuisine Classics 2 and opened up a career in food writing of their own. The couple have released seven books solely on the four branches of Cantonese cuisine.

“We keep father-in-law’s words close to our hearts and write the recipes with the attitude of academic research. Every recipe is supplemented with text about its origin and cultural significance. Because of that, for every book we wrote, we made visits to the birthplace of the food. For instance, through several separate trips, we stayed for roughly a month in total in Huizhou to complete the book Hakka Cuisine.”Exporting Chinese Cuisine To The World

In 2016, The Chans' Kitchen was invited by leading British publisher Phaidon Press to write China: The Cookbook. It assembles an impressive 650 recipes from 30 different regions. About a quarter of the recipes are of Cantonese cuisine and its branches.

The publisher even took the Chans on a promotional tour of New York, San Francisco, London, Vancouver, Sydney and Melbourne. As of now, the book has been translated into French and Spanish, with other translated versions — including Chinese — currently in the works. More than just a cookbook, it is a guide to Chinese culinary culture.

After they finished writing the recipes, the couple spent another three months writing a glossary for some ingredients unique to Chinese food, along with translated names. The Cantonese produce listed include fermented black beans, cured Chinese sausage, cured Chinese liver sausage, fermented bean paste, dried shrimp, Chinese preserved lemon and dried mandarin peel. It is a mini encyclopedia with great intellectual value.

Carrying The Torch

“The biggest impact father-in-law has on us is to cook with heart,” said Fong. “Every dish requires plenty of thinking in order to best execute it. Take the Cantonese favourite of white sliced chicken as an example. If we cook it in a hot bath, all the chicken’s flavour would be absorbed by the liquid; but if we steam it, the meat would get tough. Eventually we came to the solution to steam the chicken with a layer of cling film wrapped around it, cutting open the cling film around the thick chicken thigh so that it would cook through.

“If he had seen our current work and the published books with his own eyes, he should have been very content.”

This article was written by Agnes Chee and translated by Vincent Leung. Click here to read the original version of this story.