The air fills with a nutty aroma as a tea master, clad in a white linen smock, brings an earthenware pan close to a gas flame. With each shake of the vessel the scent deepens, until the green tea leaves she’s toasting are ready to be transferred to a teapot and steeped with hot water. After just a minute or two, we’re handed small ceramic cups of steaming hojicha tea, served with rice porridge, miso soup and a selection of Japanese appetizers.

Though it may feel more like Tokyo, we’re in the French capital, at Ogata, a space dedicated to Japanese savoir-faire — from tea and food to crafts — in the heart of the Marais. The location is no coincidence, as a breeze of Japan seems to blow through the neighborhood’s historic streets. Here, amid the fashion-forward boutiques of Paris’ 3rd and 4th arrondissements, matcha cafés and shops specializing in age-old crafts sit alongside Japanese-helmed restaurants and wagashi shops serving delicate, seasonal Japanese sweets made from rice flour and bean paste. Together they testify to the longstanding mutual fascination between France and Japan — seen in the growing community of entrepreneurs and Inspector-approved chefs who blend the cultural influences of both nations.

For Daï Shinozuka, the Hokkaido-born chef-owner of Les Enfants Rouges, the explanation for this Franco-Japanese love affair is simple. “They are probably the two most famous cuisines in the world,” he says, sitting down with The MICHELIN Guide at the French neo-bistro he opened in 2013. “The techniques are different, but in both, the matière première [raw material] is everything. A lot of importance is placed on the quality of the ingredients and respect for culinary tradition.” While Shinozuka never worked in a kitchen in his home country, he learned the tricks of the trade under chefs like Laurent Petit and Yves Camdeborde — often hailed as the father of the bistronomy movement — after relocating to France in 2007. At Les Enfants Rouges, references to his training mingle with subtle nods to Japan: hearty French classics such as duck terrine and blanquette de veau (a veal stew in a white sauce) are served alongside prune pickles, seaweed tuiles and dashi-based bouillons, and paired with a selection of Burgundian wines and sakes.

The menu at Magma is also decidedly French, despite Ryuya Ona’s Japanese roots. The chef, who originally hails from Yamaguchi prefecture and trained in Paris under Chefs Bruno Verjus and Sota Atsumi, has a penchant for fresh seafood — sustainably caught blue lobster, white tuna and his signature abalone — which he prepares in a modern French style, executed with Japanese craftsmanship.

Like the work of the master artisans so revered in his nation, no two of his menus are ever the same, as Ona dreams up new dishes for every sitting — lunch and dinner. His Far-Eastern origins, however, are perhaps most visible at the end of the meal: He forgoes the often sugar- and cream-laden sweets of his French counterparts for lighter, fruit- or vegetable-based desserts. On the day of our visit, this was translated into a creative, sweet-savory concoction featuring carrots, black olives and pecans.

Though the prestige and precision of French cuisine resonate with so many Japanese chefs, others bring the flavors of their homeland to the Marais. Back at Ogata, it’s not just the food and drinks that are rooted in Japanese tradition. In a typically Parisian hotel particulier — an urban mansion with wrought-iron balconies and exposed limestone walls — the Tokyo-based designer and restaurateur Shinchiro Ogata aims to introduce the French to the care with which he and his peers carry out everyday rituals — whether it’s brewing sencha at the Sabo tea salon, savoring a Zen Buddhism-inspired meal, or selecting handmade tableware at the in-house boutique. “At Ogata, the Japanese spirit lives in the gesture, where the intelligence of the hand expresses a culture as much as an art de vivre,” he explains. “We’re the meeting point between millenary traditions and a contemporary aesthetic.”

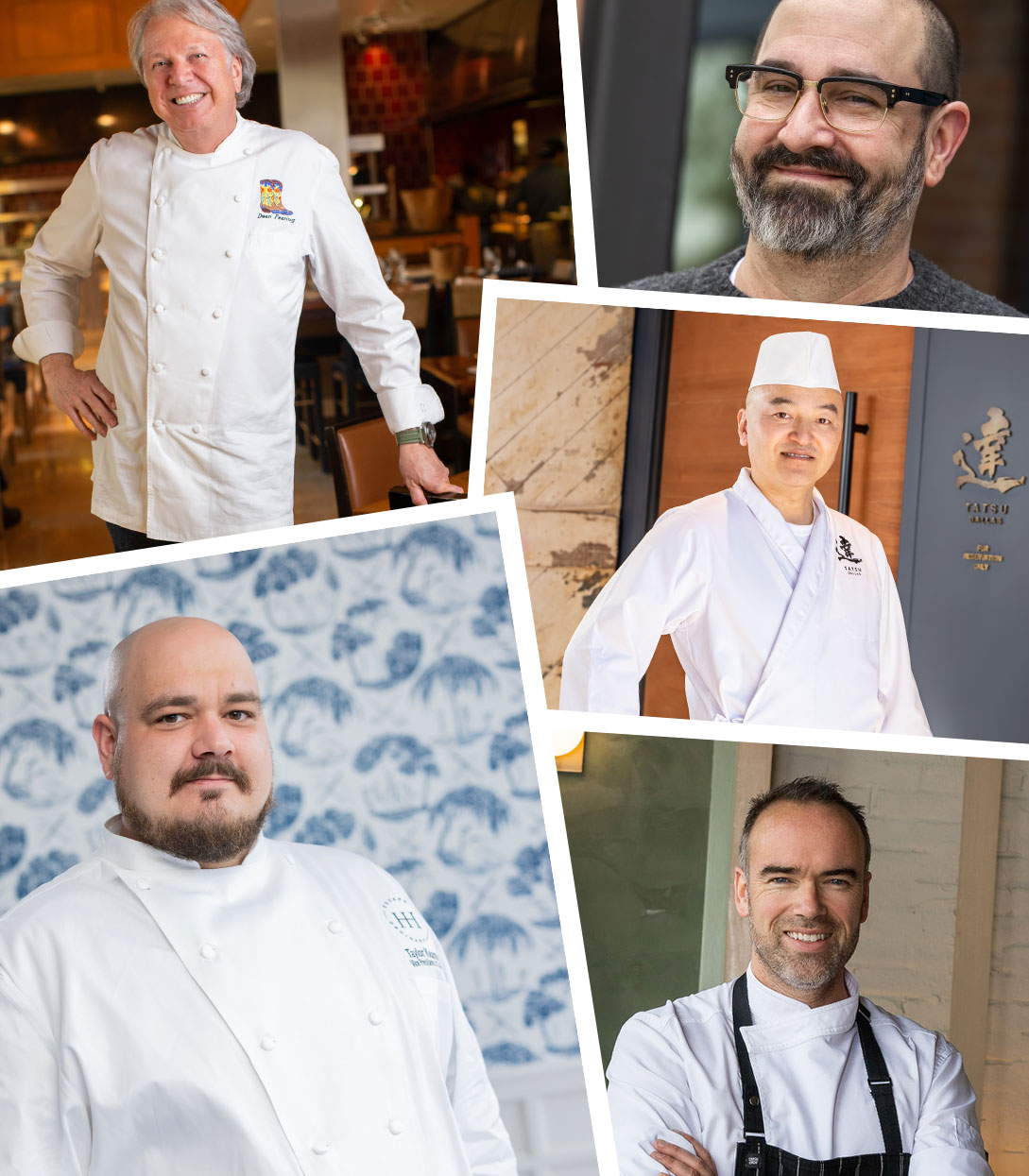

It’s this harmony between old and new that has drawn Chef Arnaud Donckele to Japanese culinary art at Hakuba, the MICHELIN-Starred kaiseki restaurant he leads at Le Cheval Blanc. Together with Chef Takuya Watanabe and pâtissier Maxime Frédéric, the trio, as Donckele puts it, “celebrates Japan in our own way, bringing our individual sensibilities, our high standards and deep respect for its ancestral art of tasting.”

“Each dish is inspired by the refined cuisine of kaiseki ryori, where nothing — textures, temperatures, seasonings — is left to chance,” he explains. “Our multicourse menus are born of a cultural dialogue and a pursuit of balance and emotion.” Witnessing the attention to detail in every bite, from bluefin tuna sushi to seasonal fruit mochi, it’s easy to understand why so many French chefs like Donckele identify with the Japanese approach — and why the Japanese, in turn, connect with the French.

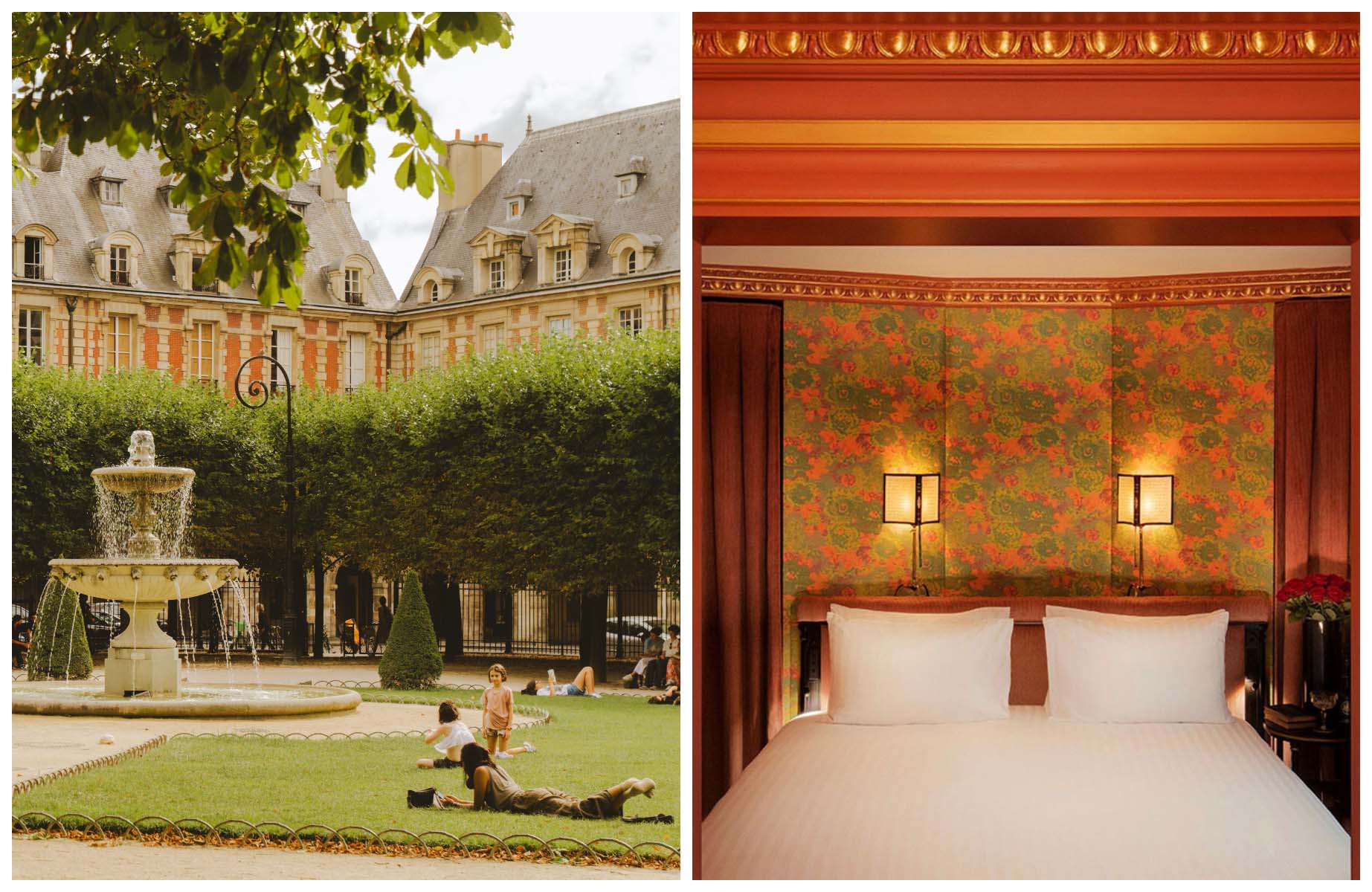

Where to Sleep in the Marais

You could end your meal at Hakuba with a warm bowl of genmaicha (green tea mixed with roasted popped brown rice), but why stop there when you can extend the experience by checking into one of the 72 rooms and suites at Le Cheval Blanc, where the restaurant is located? The art deco hotel is one of the finest in the Marais — and in all of Paris — complete with a Dior spa, a large indoor pool and sumptuous suites, some of which spread over two floors.

For a more traditional Marais stay — the area dates back to the 13th century, after all — book a room at the history-laden Maison Proust. While the design isn’t strictly Japanese, references to Orientalism, Japonisme and other popular Belle Époque styles are found throughout. Interior designer Jacques Garcia cites Asia as one of the key inspirations in his work. In the hotel’s 23 rooms and suites, this influence is evident in the richly patterned wallpapers and textiles that look as if they were taken straight from a kimono.

What to Do in the Marais

One of the earliest spots to feed the recent French appetite for Japanese flavors was Umami, a matcha café and épicerie that’s been stocking Parisian cupboards with udon noodles, furikake flakes and rice vinegars since 2014. Browse the curated products lining the shop’s shelves and it’s easy to see why it’s the go-to source for Japanese ingredients among the city’s chef crowd. “The Japanese philosophy speaks to all the big chefs,” says Roy Averty, who runs Umami alongside his wife and brother-in-law. “Once they’ve explored the French territoire, they start looking elsewhere — and Japan is often the first place they turn to.” Averty and the team also helped spark the matcha latte craze that’s swept through Paris: They were the first to serve it about a decade ago, and it remains the best place in the city to sample the drink today.

The matcha trend has paved the way for other inventive tea-based lattes. Our top pick is the hojicha latte at Dreamin’ Man, a pint-sized Japanese-run coffee shop that’s particularly popular with the Parisian fashion set. The cakes — banana breads, scones, Bakewell tarts — are just as worth trying, and the people-watching is unparalleled, especially during Fashion Week.

If all that tea-sipping has inspired you to brew your own at home, you’ll want the right vessel to serve it in. Dejima offers a well-stocked selection of Arita and Hasami porcelain alongside bamboo matcha whisks, enamel spoons and other Japanese crafts. The boutique’s French founders commission many of the ceramic designs themselves, collaborating with young illustrators from both France and Japan to bring a fresh, creative touch. Co-founder Timothée Kaplan offers another explanation for why the two cultures fit so well together. “It’s not just a love of savoir-faire — the knowledge of where, how and by whom an item is made — but also of savoir-vivre,” he says. “Both nations appreciate nice things.”

Hero image: The dining room at Les Enfants Rouges restaurant in the Marais, Paris. © Joann Pai/The MICHELIN Guide

Related articles: